What’s bad about political/intellectual elitism? It alienates everyone else from politics and critical thinking, rendering them powerless more effectively than any oppressive government could ever do. The propaganda of network TV is not more responsible for the apathy of the mainstream Westerner than the average radical leftist is. Those for whom being “political” and “educated” has become an identity, who use these terms to define themselves as a certain type of person, thus make others think that politics and radical thinking are the hallmark of a certain group of people (a drab and haughty group, at that), no more, and marginalize themselves from the rest of the world which so badly needs some of their ideas—but not their scornful “specialism,” not their divisionary attitudes and identities.

One of the Situationists’ chief goals was to fight this conception of the self according to roles played in present society (i.e. intellectual professor, indifferent bricklayer, student radical), so it’s ironic to see them used everywhere now by people who want to assert their status as members of the high political elite. Everywhere I turn now (Refused and other band lyrics and slogans, the AK Press catalog, and an even worse piece in Adbusters) I see the terms (which, since the academic language they used isn’t common, are already exclusive and exclusionary) thrown about—spectacle, detourn, derive, etc.—and the ideas misused and misrepresented by individuals who obviously have read little or none of the original texts but hope only to be impressive by citing the “latest” in hyper-radical/-intellectual French underground thinkers.

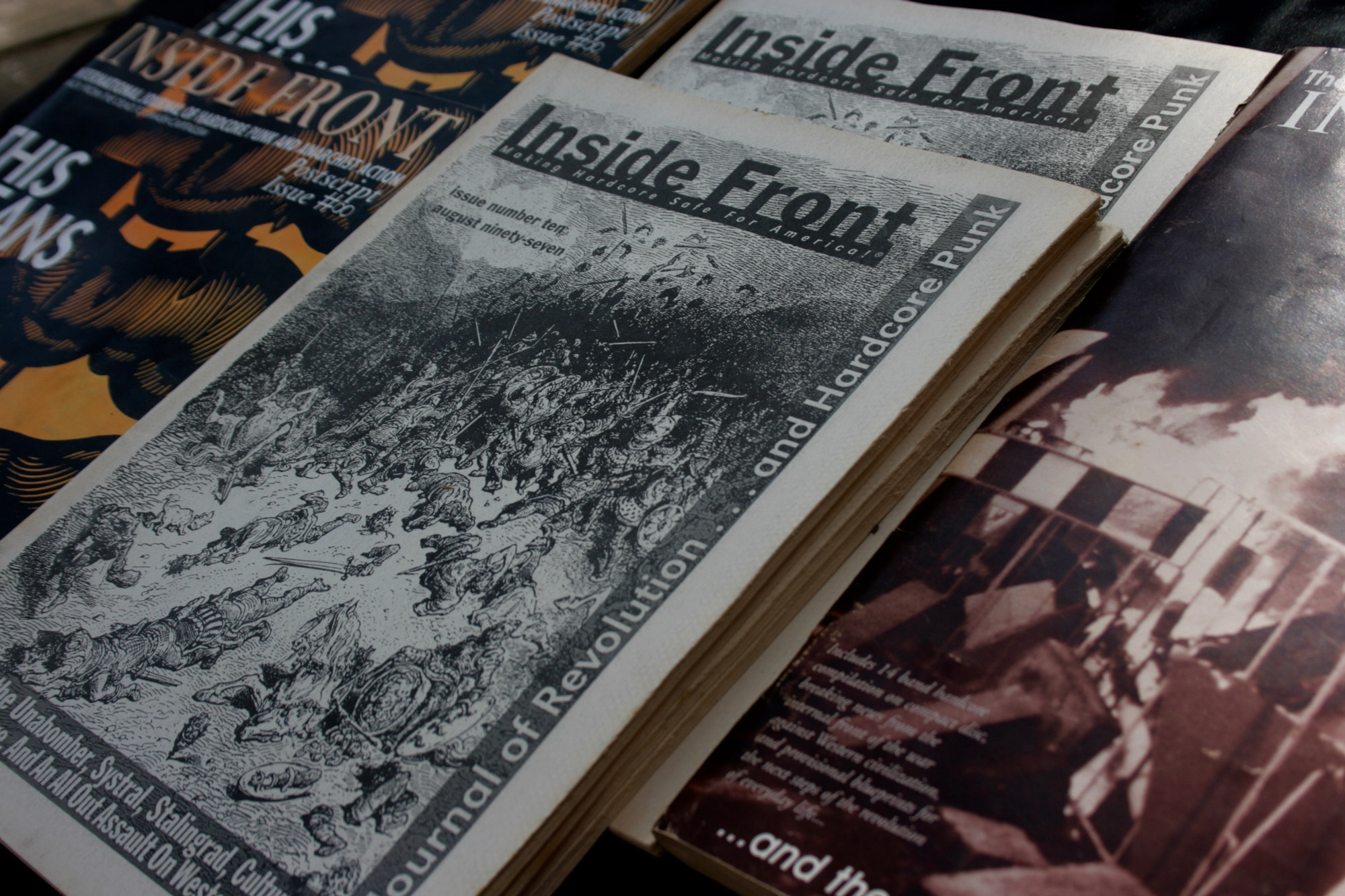

To combat this sort of thing, which ghettoizes thinkers who had ideas relevant to everyone to the most “sophisticated” of armchair revolutionary coffee-table discussions and college historical studies (which are always about putting ideas in the museum/mausoleum, rather than bringing them to new life), a straightforward, accessible, user-friendly introduction is in order. In the punk community (my thinking is that each of us travels in a few different communities, in which they know something about the needs of the people around them and can thus figure out how to act in everyone’s best interest) that should take the form of an article, in a widely read ‘zine like Inside Front.

Unfortunately, and honesty is always the best policy on these things (though a part of me would love to set up a smokescreen and just plow through this article with no regard for content, quality, clarity or responsibility) I have to admit something to you, dearest readers of Inside Front: it’s five in the morning, I’ve slept two hours a night for two weeks, I just moved out of the last house I will stay in for at least twelve months, the article is due in three hours before we leave for a ten hour drive, and I’m too fucking exhausted to write the lengthy, detailed introduction you deserve. The more I think about it, the more I realize it could be a fucking book and still not be complete, anyway. But you’re all smart kids, so our “Introduction to the Situationists” need not be more than a suggestion that you track down the original texts yourself. It would be much better for you to do the reading yourself and pursue the stuff that interests you, anyway, than to just soak up a watered-down version here.

Still, let me offer a tiny bit of background. The Situationist Internationale started as a group of artists in the late 1950’s, from a number of different nations, publishing together a magazine critiquing modern society in its various economic/social/political aspects, and meeting periodically to discuss and further refine their theory. They wanted to bring Marxism up to date, to construct a theory of what was going on in society that was preventing people from being able to live fully and act freely. The result was a critique that centered around everyday life, what happens to people and what they do on a daily basis, rather than abstract economic forces etc. The idea of the “Spectacle,” the empty roles and values and passive rituals that modern life perpetuates (and vice versa), was at the heart of this. The Situationists were characterized by a healthy opposition to ideologies, too, and denied that there was such a thing as “Situationism,” doing their best to fight off the stultifying, paralyzing effects of dogma and party line.

Early on, there was also a lot of interest in such topics as geography: how could cities be designed so they would bring the most pleasure to their inhabitants, rather than just being created randomly by “market forces” that people think of as beyond their control (when actually it is their actions that create these forces)? To pursue such questions, Situationists would go on extended “derives”: wanderings through environments designed to explore their psychological conditions. Another commonly-referred-to Situationist idea from that era is detourning: to detourn is to take an old art work, form, or formula that has a prescribed meaning in society, and, by adding some new element to it, bring out its “true” meaning: an example would be re-titling a “Dilbert” cartoon “Despair.” (You can probably imagine how that works.)

Eventually there was a falling out between the artists and the more purely radical members, who saw no hope of real art being made until after a full scale social revolution—or at least in the act of that revolution itself. Anything less was treading water, in their eyes, keeping the farce of capitalist, alienating, uncreative life afloat for one more miserable day. The artistic faction left, and the remaining group became more and more involved in perfecting their critique. In the late ‘60’s, a student group influenced by their ideas pulled some clever stunts at their university, which eventually escalated into the events of May 1968, in which the French government was quite nearly overthrown: workers joined students in a full-scale, national strike, fighting police and riot squads in the streets, refusing to recognize any authorities, asking questions in every corner of society that were usually quarantined to the radical sector… non-stop discussions were held about how a new, truly democratic society could be formed, and for a month the fate of humanity seemed up in the air.

Finally, the labor unions sold the struggle out by negotiating merely higher wages, and everyone went back to work as if nothing had happened; but that month stands as evidence of how much dissatisfaction there is in the modern world, and how it can rise to the surface under the right conditions. They don’t teach us about May 1968 in U.S. schools because they don’t want us to know that such things are possible. Most of the ideas in Inside Front are Situationist-influenced: the emphasis on how you spend your real-life time (rather than what abstractions you pledge allegiance to), how time and space are formed and controlled by the ways our present system forces us to interact, what the effects of other systems of interaction might be, all that goes back to them (and beyond, of course). The Situationists saw themselves the same way the CrimethInc. ‘workers’ see ourselves, as full-time (neither part-time nor professional) revolutionaries, with an immediate stake in things changing and no interest in getting too comfortable in the role of dissenting outsiders. Many of the slogans you see so many bands and ‘zines use (even this one) were Situationist slogans. Their influence is everywhere in our underground. That by itself is not so significant, but the fact that in their analyses of the same things we’re thinking about in hardcore punk today (consumerism, socialized roles, issues of economic exploitation and oppression, etc.) they went so much farther than most of us have yet is important. If you’re interested in ideas you read in magazines like Inside Front, one of the next places you could go to get more ideas and inspirations is the Situationists and their texts. Don’t be too intimidated by the cliquish more-anarchist-than-thou guy at your local bookshop who claims to know Society of the Spectacle backwards in Greek; they might really have something practical to offer you for your life.

Reading:

These are the books I have sitting around me as I write this:

Society of the Spectacle by Guy Debord (Black and Red, Detroit) — This starts out terrifying (insofar as it’s so abstract and theoretical that it seems to be talking about nothing, as well as being absurdly academic and dry as toast), but gets a little clearer as you proceed. If you’re going to try to learn about this stuff at all, you should eventually give it a shot, since this is one of the most central and important books to come from the Situationists; but go slowly, and with patience…

The Revolution of Everyday Life by Raoul Vaneigem (Rebel Press/Left Bank Books) — This book is equally academic and frustrating in places, but in place of Society’s blankfaced inhuman approach it is filled with the sort of passion for life and experience that Refused brought to the fore in their politics. That makes it a lot more likable, and perhaps more dangerous in the hands of young, romantic punk kids, since the insight is no less here than in Debord’s book—in my opinion, at least.

What is Situationism? A Reader edited by Stewart Home (AK Press) — This is the sort of second-hand rehash that everyone is reading. The title is a slap in the face to those of us who thought the anti-ideology aspect of the Situationist “platform” was among their most revolutionary ideas. There are some great insights and leads to follow in here, but there’s some shit as well… and even a little tiny bit of radical infighting, egotism, and careerism too, inevitably. Look past it and you’ll find, in small doses, some of the clearer summaries of and reflections on Situationist ideas and influences that you can get anywhere.

Guy Debord-Revolutionary by Len Bracken (Feral House) — This is by far my favorite critical/historical work on the Situationists. It covers a lot of the theory, with enough clarity and simplicity that it’s accessible (thank god), while also telling the life history of one of the people at the center of the whole thing. That combination of abstract ideas with factual events that played out in reality makes the stuff in here seem humanly relevant as well as theoretically right on. Yeah, this is a good book!

Enrages and Situationists in the Occupation Movement, France, May ‘68 by RenŽ Vienet (Rebel Press) — This is a blow by blow historical account, written by an insider from the radical core of the struggle, of what happened before and during the events of May 1968 in Paris and France in general. If you’re interested in seeing how the ideas we’re talking about here played out in practice, this is what you want to read… plus, it’s filled with photos of graffiti, great slogans like “Live without dead time!” that have been ripped off a thousand times in the past decade.

There’s an anthology of articles from the Situationist Internationale journal and similar writings, translated by Ken Knabb (Bureau of Public Secrets), that has real value if you want to read these guys in their own words, too. To learn more about the artistic aspect of what they were doing, especially early on (and I think this is the most overlooked aspect of the Situationists, and wrongly so), you might be able to go to a university art library and look for catalogs from retrospective exhibitions, etc. If you’re interested in this stuff and want to go into any more depth, but can’t find the resources, just write us and we’ll photocopy or steal you more stuff.